Is he a ghost, or is he a hallucination?

That was the question I woke up with after the dream. In it, I met a noble man I did not recognise but somehow knew: eyang, my ancestor. He spoke calmly, without urgency, telling me to reconnect with my Majapahit lineage and, more importantly, not to forget where I come from. The scenery was almost similar to the painting above, so when I woke, I dismissed it. Perhaps I watched something, and it seeped into my sleep.

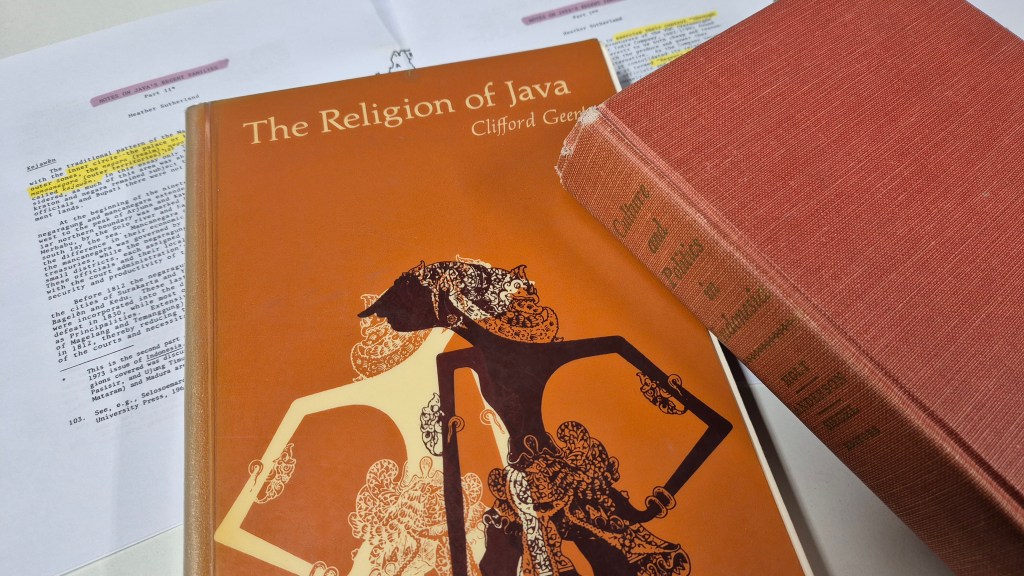

My family had always been reluctant to talk about lineage, and I had never been told anything about it. Still, the dream lingered. For fourteen years it sat quietly in the background of my life. Other dreams appeared at unexpected moments, leading to several curious trips to temples (candi), but left me perplexed about why they mattered so much when I had no proof they should. My attempts at meaning-making through reading books on Javanese-Balinese philosophy and Majapahit history could only explain half of what I experienced. I did not dare to wonder that I might be related to significant figures. Or, I did not know what to wonder, speaking from someone who is not fluent in Javanese and who did not realise that a city named Mojokerto exists until hearing it in a dream.

It was only after my grandmother passed away that everything shifted. While sorting her belongings, my parents found an official document that traced our family lineage. There it was, written plainly, confirmation of what had once felt almost impossible to verify. I know now the missing link; exactly where to look and which trail to follow. The discovery did not feel dramatic or triumphant; I was simply relieved that I trusted my intuition thus far. Looking back, those dreams were a series of invitations—one I had been responding to unknowingly for years—to pay attention to a way of being that had shaped me long before I understood where it came from. This essay is my answer, using what I do best: academic work, exploring old literature that is surprisingly more accessible when I am 7,000 miles away from home.

The document itself revealed that my great-great-grandfather was Raden Tumenggung Notodiningrat I (1820-1839), the first regent (bupati) of Malang, who governed a region in the extreme east (Ujung Timur) of Java, an area historically significant for the Blambangan and Singhasari kingdoms, with close ties to the Balinese culture. The patrilineal line was succeeded by Raden Adipati Aryo Notodiningrat II (1839-1883) and Raden Tumenggung Aryo Notodiningrat III (1883-1898), before the position was passed on to relatives from the Nitiadiningrat line of Pasuruan (Sutherland, 1973; Sutherland, 1974).

This makes me the eighth generation from R.T. Notodiningrat I, though the significance of this status ended after Indonesian independence in 1945. My mother and I also do not have titles before our names because—thankfully—since the sixth generation, children have been able to marry for love, free from the duty to preserve nobility. Likewise, learning this did not feel like uncovering a prestigious inheritance. If anything, it felt quietly grounding. It did not give me a new identity to claim, but sharpened an inner sense of duty that had already been there, though long unrooted in reality.

The regent belonged to the priyayi class, a Javanese administrative elite whose legitimacy rested not only on office but also on ethical conduct. In East Java, including Malang, priyayi genealogies often trace back to the Majapahit kingdom and figures such as Prabu Brawijaya V (1468-1478). I understand this not as a biological claim or as a means to revive the days long gone, but as a symbolic gesture. For me, this memory operates simply as a reminder of the past that I have to nurture, not through pride, but through a life worth remembering; a personal history to be passed on through generations as an inevitable facet of my Javanese identity.

More importantly, unlike royalty, which was strictly determined by direct bloodline, regents were chosen based on multiple factors. Priyayi authority was not meant to be asserted or “performed,” but exercised through smooth (alus) decorum: careful speech, emotional equanimity, and the ability to mediate rather than dominate. Ethics were not rules imposed on power, but they were the conditions that made power acceptable in the first place. Their legitimacy was inseparable from self-discipline, which compensated for their “thinner” blue blood (Geertz, 1960; Sutherland, 1975).

“The quality which the priyayi have traditionally stressed as distinguishing them from the rest of the population is that of being halus. […] Smoothness of spirit means self-control, smoothness of behaviour means politeness and sensitivity. Conversely, the antithetical quality of being kasar means lack of control, irregularity, imbalance, disharmony, ugliness, coarseness, and impurity.” (Anderson, 1960, p.38)

I was struck not by how foreign these values felt, but by how familiar they already were in my own life. Long before I knew anything about my lineage, I had always gravitated towards self-reflection, choosing to correct myself rather than others to attain peace, because what is peace if not inner peace? I do not speak ill or show anger; I leave quietly, honouring each person’s path to growth that sometimes no longer intersects with mine. My YouTube channel introduction uncannily reads, “For those who live softly in a world that shouts. Because not everything needs to be loud to be heard.” It is as though someone from a distant past taught what I had only learned recently—two days ago, to be exact.

This ethical orientation differs from the dominant Western approaches. Many Western ethical schools of thought, from Kantian deontology to Mill’s utilitarianism, emphasise explicit principles through formal structures (Beauchamp, 2001). Moral behaviour is often framed as adherence to universal norms or compliance with codified standards. Authority, in turn, is legitimised through laws and guidelines. Priyayi ethics, by contrast, are not primarily rule-based or declarative. They are inward, situational, and relational. Ethical judgement is less about asserting what is right and more about sensing what is appropriate (Geertz, 1960; Errington, 1984). Rather than asking, “What rule applies here?”, priyayi ethics ask, “How should a wise person act in this situation?”

Before continuing, I need to clarify regarding my use of the term “priyayi ethics.” The references do not frame priyayi values as an explicit ethical system, nor did the priyayi themselves articulate their conduct in the language of moral philosophy. What I describe instead are normative expectations of behaviour; ways of shaping the self that govern what can and cannot be done. The closest term would be tata krama, which is frequently translated as etiquette. However, it represents a much deeper system of conduct that moulds the rules of discourse and precedence of a priyayi (Errington, 1984; Bertrand, 2008).

This difference also shapes how power is understood (Anderson, 1972). In Western political and organisational cultures, visibility, direct articulation, and overt strength are often seen as markers of leadership. Nevertheless, in the Javanese priyayi system, power weakens when it must be displayed. Authority is strongest when it is composed, indirect, and unforced, such as when giving perintah halus, orders given in language so polite and indirect that they were felt as requests, and yet, they were taken with absolute authority, automatically setting actions in motion. As Bertrand (2008) adds, for the priyayi, power should speak for itself.

“Ideally speaking, a priyayi was a well-born Javanese holding a high government office, thoroughly versed in the aristocratic culture of the courts. He should be familiar with classical literature, music and dance, the wayang kulit (puppet shadow play), and with the subtleties of philosophy, ethics, and mysticism. He should have mastered the nuances of polite behaviour, language and dress, and, until well into the late nineteenth century, he was expected to be at home in the arts of war, skilled in the handling of horse and weapons. In addition to these acquired skills, the priyayi was meant to be a man of integrity and honour.” (Sutherland, 1975, p.58)

Furthermore, Errington’s (1984) work gave language to something I had lived but never articulated. Rather than treating priyayi ethics as an etiquette or a leadership lesson, he describes them as a discipline of the self. Ethical conduct (lahir) is understood as the outward expression of an inner state (batin). Refinement (alus) is not performance, but evidence of a constant awareness (eling). To the same degree, ethical failure is not breaking rules, but forgetting oneself (lali). A priyayi, therefore, would train by looking inward, eroding the crude ego (aku) to cultivate the divine spark within (ingsun). This was achieved through rigorous self-control and disciplined asceticism, practices that sharpened their deep intuition (rasa) while training them to master their feelings and to restrain worldly impulses.

Tata krama is precisely the practice to demonstrate a refined and controlled inner state, rather than the other way around. Javanese ethics operate less as intentional moral choices than as embodied dispositions formed through everyday practice. Ethics, in this sense, acts as a tacit inner compass that precedes conscious, logic-driven calculations (Bertrand, 2008). We do not learn to swim by memorisation of the movements; instead, the rasa of being in the water is what truly teaches us.

Relearning these comes with a persistent sense of responsibility: not to let down those who came before me. Not because of names or titles, but because they were people who once trusted, relied on, and looked up to. If someone before me lived a dignified life, then at the very least, I must let it continue through how I spend my time here while I am alive. While this is ideal for every human being, the sense of urgency was magnified and multiplied the moment I found that missing piece. Those unseen eyes are probably on me.

That being said, priyayi ethics, as I understand them, are not about exclusivity, hierarchy, or moral superiority. They do not belong only to those with titles or lineage, nor do they grant anyone the right to judge others. In fact, they point in the opposite direction. The core of this tradition lies in the belief that the first responsibility of any leader is to govern oneself by cultivating self-control (mawas diri), awareness (eling), and care (tepa slira) before attempting to influence others (Errington, 1984). The state of the inner self directly mirrors the state of the regions. This way, personal weakness was believed to weaken the governed areas, including the people and the system. Authority is never something one claims over people, but something one earns gradually through the endless consequences of actions. It is less about who one is and more about how one lives; an ethic that remains open and relevant to anyone willing to practise self-discipline in everyday life.

This way of thinking also represents how I relate to money. Historically, priyayi were not defined by personal wealth in the modern sense. Their security came less from accumulation and more from access to education, stable roles, and opportunities that allowed them to live according to their inherited duty (dharma) (Sutherland, 1975). Within priyayi ethics, excessive pursuit or display of wealth was often viewed negatively, as a sign of poor self-restraint and misaligned priorities rather than success. To signify wealth too openly risked undermining one’s credibility. So, naturally, their values were seen as opposing those of merchants (saudagar) (Errington, 1984; Bertrand, 2008). Selling meant thinking about profit, not about society, which also explains their proclivity for humanitarian aid (Geertz, 1960). To them, true wealth is attracted to those who possess cosmic power (kasektèn), which can be seen from the divine radiance (wahyu) that emanates, again, from the inside (Anderson, 1960).

I recognise this orientation in myself. I am motivated less by money as an end than by what it enables: independence, education, health, and the freedom to choose. Money matters to me insofar as it supports a contented life, not as an ultimate quest. Reconnecting with the priyayi ethics, then, is not about reclaiming hierarchy or romanticising the past. It is about recognising the value of small, deliberate practices, such as choosing reflection over reaction, influence through example rather than dominance, continuity over disruption, and integrity even in private moments. These values already shape how I operate, whether in everyday life, in relationships, or in research.

There is a subtle irony that much of my academic work focuses on AI ethics, particularly on how ethical frameworks might be shaped from below, embracing pluriversal perspectives that encourage local forms of sovereignty. Much of this thinking has been informed by globally circulating critical theories, including those from Africa and India. Yet, in tracing my own lineage and revisiting priyayi ethics, I realised that many of the values I argue for—context-sensitivity, personal duty, relational responsibility, and ethics as lived practice rather than abstract rule—have long existed within Javanese ethical traditions. Perhaps the question is not only how to decolonise AI ethics at a theoretical level, but also how willing I am to recognise and relearn the ethical frameworks already embedded in my own cultural history. In that sense, learning more about Javanese ethics may be just as important as engaging with another major theoretical framework.

The priyayis were shaped by strict self-governance, guided by norms, rules, and regulations that permeated both their personal and social life, forming an extensive list of precepts that disciplined their everyday behaviour (Bertrand, 2008). In contrast, in terms of relating to others, they were expected to display sensitivity and subtlety or“tanggap ing sasmita,” the cultivated ability to read what is not explicitly said, to attune oneself to others’ inner states, and to act in ways that preserve social equilibrium (Errington, 1984). Therefore, ethical action was always context-based, enacted through careful interpretation. Additionally, central to this self-governance was the rejection of selfish interest or personal gain (pamrih). The principle of “sepi ing pamrih, rame ing gawe” meant to hush one’s own interests and devote oneself entirely to duty. A regent’s authority depended on the absence of pamrih. Once it became apparent, his radiance (tédja) was believed to fade.

Read alongside contemporary concerns, this offers a powerful lens for AI ethics: trustworthiness emerges from systems that are transparent and free from concealed interests. Just as pamrih undermined a regent’s legitimacy, hidden commercial motives or extractive logics diffuse the integrity of AI systems. This leads to interesting follow-up questions: can I find the Javanese counterpart of the African ubuntu concept (Gwagwa, Kazim, & Hiliard, 2022; Mensah & Van Wynsberghe, 2025) that can also be translated to the broader AI ethics discourse? Is it tanpa pamrih, eling, or the core of it all, alus? What if the eling-lali axis is framed as two poles: “remembering appropriate orientation” and “losing track of purpose” to ensure alignment? Lastly, just as Anthropic hired a philosopher to create the Claude 4.5 soul document (Tangermann, 2025), what if the model were trained with priyayi ethics? What contraints and affordances would emerge? Beyond that, considering how to accurately convey ethics encoded in linguistic practices foreign to English—and whether AI systems could truly grasp them—underscores what we lose by universalising AI ethics.

In my PhD research proposal, I wrote—likely out of inferiority—that Indonesians are unfamiliar with the study of ethics, let alone the ethics of technology. Contemporary Indonesians are raised in an environment where ideas of right and wrong are almost always framed in religious terms. Ethics, as a separate concept, is never explicitly taught to us. Instead, we learned to follow laws and instructions from the holy book and religious figures. For a long time, I assumed this meant that ethical discourse was absent from everyday life. Yet revisiting priyayi traditions has led me to a different realisation: perhaps ethics was always there, unconsciously shaping ways of being and doing, simply unnamed and untheorised. Understanding ethics as an embodied, contextualised practice—rather than a doctrine—offers a way to think about AI ethics not as an external imposition, but as a shared responsibility among all actors, human and non-human, involved in shaping a more cohesive society. Unbeknownst to me, it is always heading towards more-than-human alignment (manunggal) (Anderson, 1972).

Another aspect of priyayi ethics that resonates deeply with my work is the role of mediation. Historically, priyayi were not sovereign rulers but brokers; positioned between the centre and the provinces, the Dutch Binnenlands Bestuur (Interior Administration) and the native population, Islamic and Javanese values, authority and social harmony. Their responsibility lay in translating, smoothing, and holding tensions rather than enforcing decisions from above (Sutherland, 1975). This mediating role helps me understand why priyayi ethics feel more like a relational practice rather than a moral theory, aligning with my preferred paradigm in the philosophy of technology. In my research, drawing on Peter-Paul Verbeek’s notion of moral mediation, ethics is not imposed externally through rules but emerges within the relations between technologies and humans (Verbeek, 2006; Smits et al., 2022). This parallel makes the connection between my lineage and my research feel less accidental. I see it as a continuity of ethical orientation across very different contexts, reshaping how I view and approach the subject.

In the end, discovering my regent lineage will not change who I am, but it has clarified why I am the way I am. It offered an inner compass made out of karmic connections. If that past is to remain alive, it will not be through titles or institutions, but through the soft ways it continues to shape how I conduct myself. Tata krama, then, becomes a way of living attentively within these mediations, by being aware that every action carries consequences, and every form of power, human or technological, demands restraint.

As I end this writing, I realise that the krama inggil whisper that I have never understood before is probably this: “Ethics does not begin with naming or thinking; it begins with how one lives. Live well, my great-great-granddaughter, and your world will no longer be in chaos.”

REFERENCES

- Anderson, B. (1972). The idea of power in Javanese culture. In Culture and Politics in Indonesia (pp.1- 70). Equinox Publishing.

- Beauchamp, T. L. (2001). Philosophical ethics: An introduction to moral philosophy. McGraw-Hill.

- Bertrand, R. (2008). A Foucauldian, non‐intentionalist analysis of modern Javanese ethics. International Social Science Journal, 59(191), 75-93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2451.2009.00681.x

- Errington, J. J. (1984). Self and self‐conduct among the Javanese priyayi elite. American Ethnologist, 11(2), 275-290. https://www.jstor.org/stable/643851

- Geertz, C. (1960). The background and general dimensions of prijaji belief and etiquette. In The Religion of Java (pp.227-260). University of Chicago Press.

- Gwagwa, A., Kazim, E., & Hilliard, A. (2022). The role of the African value of Ubuntu in global AI inclusion discourse: A normative ethics perspective. Patterns, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2022.100462

- Mensah, J. O., & Van Wynsberghe, A. (2025). Where are the missing values: An exploration of the need to incorporate Ubuntu values into African AI policy. AI & Ethics, 5, 4365–4375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-025-00746-0

- Smits, M., Ludden, G., Peters, R., Bredie, S. J., Van Goor, H., & Verbeek, P. P. (2022). Values that matter: A new method to design and assess moral mediation of technology. Design Issues, 38(1), 39-54. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00669

- Sutherland, H. (1973). Notes on Java’s regent families: Part I. Indonesia, 16, 113-147. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350649

- Sutherland, H. (1974). Notes on Java’s regent families: Part II. Indonesia, 17, 1-42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350770

- Sutherland, H. (1975). The priyayi. Indonesia, 19, 57-77. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350702

- Tangermann, V. (2025, December 3). Anthropic’s soul overview for Claude has leaked. Futurism. Retrieved from https://futurism.com/artificial-intelligence/anthropic-claude-soul

- Verbeek, P. P. (2006). Materializing morality: Design ethics and technological mediation. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 31(3), 361-380. https://doi-org.eux.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/0162243905285

https://pandjipainting.wordpress.com/2009/01/12/bedhoyo-ketawang/

Leave a comment