The rise of Generative AI presents a dilemma due to the public’s pragmatic acceptance of AI-generated design works (M=5.33, SD=1.89), alluding to the possibility of creative labour displacement. Grounded in Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma and Mori’s Uncanny Valley, this study examines how the Indonesian public perceives the ethical and utilitarian tensions of AI adoption. Using a sequential explanatory mixed-methods approach, an online survey (n=553) was conducted with respondents aged 20 to 50 in 10 Indonesian cities. Participants evaluated four case studies—advertisement, book cover, Instagram post, and photo manipulation—alongside their general sentiments. Findings indicate lower acceptance of GenAI for commercial (M=4.78, SD=1.84) than for personal use (M=5.43, SD=1.58), and concerns about GenAI’s potential to replace designers (M=5.2, SD=1.70). The lowest receptivity was observed in video and photo manipulation, reflecting the uncanny valley effect. Meanwhile, respondents tend to justify the use of GenAI when there are no formal regulations, thereby diminishing their ethical concerns, while also exhibiting difficulties in identifying AI-generated images. These perceptions underscore the importance of AI governance in protecting human designers from being replaced by machines and ensuring the authenticity of design works.

This is an excerpt from a published paper in “Jurnal Sosioteknologi” https://doi.org/10.5614/sostek.itbj.2025.24.3.8

INTRODUCTION

Generative AI (GenAI) disrupts creative industries by offering faster, more affordable, and more accessible alternatives to traditional creative processes, appealing to non-professionals. This shift exemplifies Christensen’s (1997) Innovator’s Dilemma, where emerging technologies challenge established professional practices, particularly those that have reached the mature stage. While this disruption may not directly lead to company failures in the creative industries, it raises concerns about creative displacement, where AI could partially or fully replace creative roles (Caporusso, 2023; Erickson, 2024). However, in the context of the Technology S-Curve (Christensen, 1992), GenAI is still transitioning between the emerging and growth stages, providing opportunities for studies to inform and shape its future trajectory.

GenAI can be used throughout the creative process, including information analysis, content creation, and content enhancement (Anantrasirichai & Bull, 2021). It can also be implemented in various creative industries clusters, ranging from poem writing (Hämäläinen, 2018), dance collaboration (Trajkova et al., 2023), music composition (Déguernel et al., 2022), drawing (Ibarrola et al., 2022), interior design (Hsieh et al., 2022), fashion design (Kim et al., 2024), to game design (Yang et al., 2024). These studies indicate that integrating GenAI is not a straightforward process from prompt to product, but rather, it closely involves designers in a long, iterative process. Apart from its most common use in ideation, creatives also utilise it to elevate their works and expand beyond their comfort zone, supporting the notion that GenAI works as a complementary tool to creativity (Erickson, 2024).

Still, this does not exclude challenges in GenAI adoption, particularly in the Indonesian context, with an overall AI readiness index of 39.3 out of 100, lagging behind other Asian countries such as Singapore (70.1), Japan (59.8), India (49.8), and Malaysia (47.3) (Salesforce, 2023). While navigating other issues such as copyright infringement by artificial agents (Jiang et al., 2023), low wages, and unstable gig-based projects (Shumakova et al., 2023), creative professionals are expected to adapt to the increasingly complex technology (Pearson, 2023) and even become subservient to it (Park, 2024). This could lead to greater inequality in the creative industries, affecting those who do not have access to GenAI in the first place (Anantrasirichai & Bull, 2022), as Indonesia also struggles with a lack of digital talent (Rukmorini, 2023).

Indeed, the democratisation of GenAI enables anyone to gain an ability that was once exclusive to creative professionals (Park, 2024); however, it is also essential to assess its associated costs. For example, there have been growing concerns about copyright infringement on datasets used to train GenAI models (Murray, 2023; Samuelson, 2023), homogenisation (Boutier, 2025), gender biases (Locke & Hodgdon, 2024), and cultural biases (Karpouzis, 2024) in the context of prompt translation. While there are existing computer-aided tools to assist creative endeavours, such as AutoCAD, unlike GenAI models, they do not possess the ability to create something new from prompts alone (Pearson, 2023). As a result, when the boundaries between amateurs and professionals are becoming blurred (Lee, 2022), there is a need for empirical ethical guidelines and policies that protect the most affected parties, in this case, artists and designers, by studying both the general public’s and creative professionals’ perceptions towards GenAI. This paper covers the first.

For instance, the UK and China conduct consumer and industry research to inform their policy-making processes, ensuring an evidence-based approach (Shumakova et al., 2023), as there is no one-size-fits-all solution that can be implemented globally (Óhéigeartaigh et al., 2020). The nuances of cultural and socioeconomic differences must be considered, rather than forcing them to adapt to regulations made by developed countries that may not be entirely relevant (Carillo, 2020; Keith, 2024).

In terms of ethics, Vesnic-Alujevic et al. (2020) classify it into individual (autonomy, dignity, data protection) and societal (fairness, accountability, and transparency, among others). However, ethical guidelines serve only as guidance and have no legal standing or reinforcing mechanism, highlighting the importance of laws and policies in ensuring ethical practices (Carillo, 2020; Hagendorff, 2020; Putra, 2024). This more binding approach is planned to be adopted by Asian countries, including Indonesia (Juwita, 2024; Xu et al., 2024).

The creative industries comprise multiple clusters, each with varying receptivity to AI and distinct governance needs. The study of machine anthropomorphism, particularly through Mori’s uncanny valley theory (1970), helps explain how AI-generated content is perceived across these sectors. This theory suggests that when non-human entities, such as robots or AI-generated visuals, reach a certain degree of human resemblance, they may evoke unease rather than acceptance, hindering interaction. This effect has been observed in chatbot communication, where interactions that feel too human-like can create discomfort (Ciechanowski et al., 2019), and in prosthetic hand design, where a more mechanical appearance is often preferred over an overly human-like skin texture, despite both serving the same function (Mori et al., 2012). As machines now generate creative works that closely resemble human-made content (Männistö-Funk et al., 2018; Mara et al., 2022), this study applies the uncanny valley theory to assess public perception of AI-generated images, particularly in relation to the concept of uncanniness.

Based on the theoretical framework, this paper answers three research questions:

- What are the public sentiments and attitudes towards AI-generated design works?

- What are the perceived advantages and limitations of using GenAI in the creative industries?

- How likely is it for GenAI to replace designers?

Besides general sentiment, the study evaluates respondents’ acceptance of four case studies: a video advertisement, a book cover, a social media illustration, and an illustration. It also measures the respondents’ ability to distinguish AI-generated works from authentic human-made ones. These illustrations of GenAI usage are hoped to equip them to answer RQ2 and provide clear reasons behind their choices. Finally, RQ3 presents a hypothetical situation to help reflect on the possibility of creative displacement from an outsider’s perspective, as what creatives might see as threats could be viewed as opportunities by the general public, as shown by the findings. The presence of GenAI exacerbates the already exploitation-vulnerable working conditions of creative professionals, such as long hours, inadequate wages, and delayed compensation, particularly since many of them are freelance workers (Izzati et al., 2021).

This study frames the designer’s dilemma as both a disruption and a catalyst for redefining creative roles. Rather than replacing designers, GenAI should be able to enhance human creativity, supporting Lee’s (2022, p.602) view that it offers a chance to “rehumanise creativity,” when the human labour and original ideas becomes more respected, for instance, the increasing price for authentic human-made design, in contrast to merely capitalising creative works as commodities regardless of authored by humans or machines, which might “dehumanise creativity.” Ultimately, this study underscores the need for more scholarly research and policies in the Indonesian creative industries, as well as the importance of cluster-specific regulations. For example, the implementation of GenAI in music and movie clusters deserves its own study.

Previous reports have examined overall AI readiness (Salesforce, 2023), preparedness (IMF, 2023), government AI readiness (Nettel et al, 2024), responsibility (Adams et al., 2025), and impacts on jobs (Gymrek et al., 2023), but do not specifically address the creative industries. Therefore, the novelty of this research lies in the exploration of public sentiment towards text-to-image—rather than text-to-text—GenAI in the Indonesian design field, which remains largely unexplored in existing literature.

A key limitation of this study is its focus on urban respondents, which may not fully capture the perceptions of Indonesia’s broader population, particularly those in rural areas or with lower digital literacy. Future research will focus on designers, examining their interaction and relationship with GenAI, as well as their response to this designer’s dilemma, to complement the public perspectives presented in this study.

METHOD

[…]

DEMOGRAPHY & GENAI FAMILIARITY

[…]

PERCEPTION TOWARDS CASE STUDIES

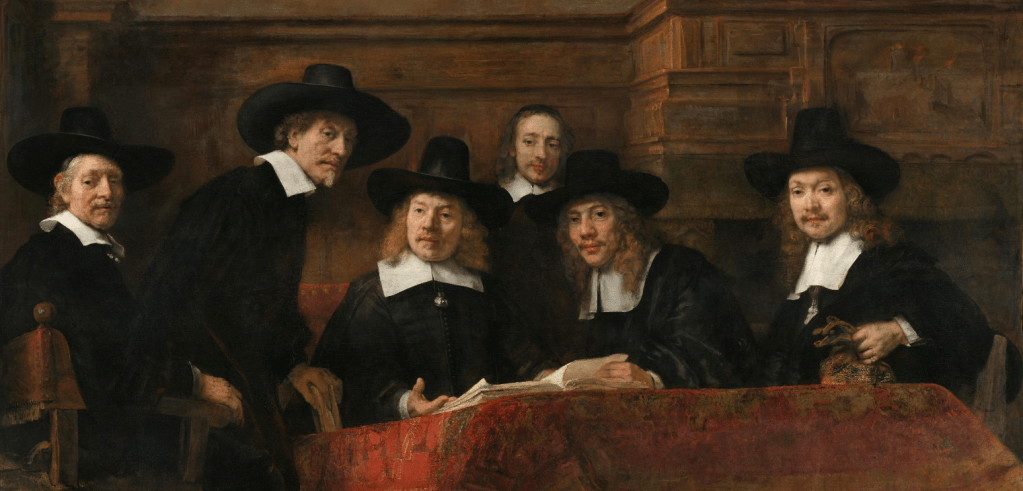

The survey evaluates four case studies of existing commercial GenAI usage in Indonesia. The first is a video advertisement made by ExtraJoss—an energy drink company—depicting the success of an Indonesian football team to invoke national pride. The second consists of two fiction book covers published by Marjin Kiri, and the third is a culturally rich Instagram post illustration for the @filsafathindu account. The image is accompanied by a lengthy caption that explains a specific concept of the religion to online audiences, highlighting the supplementary role of the image. The fourth is a promotional image for RupaAI, an AI-powered photo manipulation tool that offers paid services to enhance the portrait quality of its users. All images are shown in Figure 3.

Compared to a previous study on AI-generated artworks (Wiradarmo & Azhar, 2025), which reported an overall mean of 4.75 (x̄ SD = 1.89), respondents are more receptive towards AI-generated design works, with a 0.46-point increase in the overall mean to 5.21 (x̄ SD = 1.64). This exemplifies that GenAI should be evaluated differently in the art and design fields, as both possess distinct natures and operate in separate ecosystems. Table 1 details the scores for each case study, with the highest public interest in video advertisements (M = 5.42, SD = 1.50) and the lowest, yet still highly valued, being in Instagram post illustrations (M = 5, SD = 1.80). After all, the most frequent value in all cases is 7.

The follow-up qualitative questions unveil contrasting reactions that echo previous research, where perceptions change after disclosing that the artworks are AI-generated. Interestingly, the change does not only come from reluctance but also amazement towards the AI’s capability, which increases some respondents’ interest (Wiradarmo & Azhar, 2025). Respondents acknowledge the detailed, realistic, and eye-catching visuals in the video advertisement case, which pique their high interest. On the other hand, some respondents have strong negative reactions to the monotone expression and the absence of human emotion in the production, such as a less engaging storyline. This might be because the video has no dialogue, only a voiceover over a compilation of short videos.

The second-highest receptivity is for photo manipulation as long as it is utilised for personal use. The high score stems from relatability, as respondents often struggle to provide professional-looking pictures, such as those for LinkedIn profiles. Using AI is a practical way to enhance the quality of an already existing photo. However, this does not erase concerns regarding unrealistic portrayals, which are perceived as misleading or fake and potentially deceiving. Some also draw boundaries of usage based on the user. For instance, a CEO or a politician should be prohibited from using AI, as they should have the financial means to craft an authentic self-branding.

The book cover case drew adverse reactions from book communities on social media, which led the book publisher to state that they are open to using AI in publishing (Novrian, 2024). In the survey, while respondents acknowledge the aesthetic appeal of the book covers, they still have concerns about bypassing human designers to save costs, which decreases their enjoyment. Some respondents also convey similar suggestions regarding the AI user, distinguishing between the ethical responsibility of established publishers and self-published authors.

The result from the Instagram post case is unique because rather than evaluating AI-generated illustrations for social media in general, the majority are worried when AI is instructed to represent culture and religion, as these are context-sensitive subjects that demand accuracy. Since most of them are not from Hindu backgrounds, they are more reluctant to give elaborate opinions. Moreover, the image is considered the most realistic among others, but evokes an uncanny feeling as it is seen as too artificial, too polished, or too typical of an AI. Still, the interest rate would likely increase if the presented case were not related to religion.

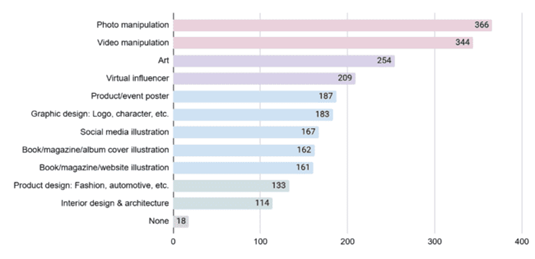

Regarding uncanniness, the survey provides tick boxes to note which GenAI application makes the respondents uncomfortable. The result is presented in Figure 4, with photo and video manipulation scoring the highest, specifically when used to manipulate other people’s images without their consent. With the addition of virtual influencers, these three resemble the uncanny valley theory, proving that there is indeed a threshold of accepted realism.

Meanwhile, art is uncanny in terms of emotional meaning rather than appearance, as viewers expect an emotional connection, not only based on interpreted messages but also relatability, for example, through the artists’ personal lives (Wiradarmo & Azhar, 2025). Another study shows that viewers’ value perception decreases when they are informed that an artwork created by a human is actually generated by AI (Fortuna & Modliński, 2021; Chiarella et al., 2022). In contrast, graphic design works such as posters and social media illustrations require a more surface-level aesthetic. As long as the message or purpose is conveyed well, respondents have less expectation of resonating with the works or seeking underlying meanings.

The uncanniness score decreases in parallel with the complexity of the final output. For instance, in interior design and architecture, there is still a lengthy process of creating technical drawings, mockups, and physical construction. There are many iterative improvements to ensure that AI-generated images can be realised in real life, primarily related to the engineering aspect. Product design, meanwhile, often integrates user feedback in several loops of testing phases. For these fields, AI involvement is still limited in the early stages, unlike graphic design, which can generate images with minimal editing and refinement, leading to another facet of uncanniness regarding human-like machine involvement.

GENERAL PERCEPTION

[…]

SENTIMENT

[…]

COMMERCIAL USE

As depicted in Figure 7, respondents generally approve of GenAI in commercial settings, as long as it adheres to existing laws and respects intellectual property rights. For example, some say:

- “It is fine, but with a side note that there must be rules for commercial uses.” (R454, non-CI)

- “No problem, as long as it follows applicable laws and regulations.” (R025, non-CI)

- “It is okay, as long as it does not violate the copyrights of other people’s works, because imitating someone’s hard work that GenAI did not create is still unethical.” (R536, non-CI)

Unfortunately, there are currently no specific regulations governing the use of GenAI in the Indonesian creative industries, nor are there guidelines in place to ensure public awareness of copyright laws. This regulatory vacuum presents another dilemmatic circumstance and ethical ambiguity as encapsulated by these arguments:

- “Because the government issues no prohibition concerning the usage of GenAI.” (R063, non-CI)

- “It is not a violation, and there are no laws regulating it.” (R181, non-CI)

- “No legal protection.” (R478, author)

It is worth noting that most of these perspectives originate from individuals outside the creative industries, whereas R478, an author, implies a pessimistic tone. Some believe that since no official law prohibits the use of AI in creative industries, its use remains both legally and ethically permissible. This attitude suggests an assumption that there is no moral responsibility without legal responsibility. If there is no law directly and specifically prohibiting AI-generated works, they are considered acceptable for commercial use.

Related to this matter is the opinion on transparency in AI-generated content, especially in commercial settings. A graphic designer (R482) suggests that AI-generated works should include a disclaimer to prevent misleading audiences or harming other creators. This aligns with growing calls for more explicit guidelines (Carillo, 2020; Keith, 2024) and labelling of AI-generated content in the creative industries (Witttenberg et al., 2024). Likewise, a previous study found that the rising acceptance of AI artworks is contingent upon proper credit being given. In other words, viewers simply do not like being lied to (Wiradarmo & Azhar, 2025).

For creative professionals, GenAI has the potential to streamline creative production and reduce workload, as it is perceived as a promising technology that produces high-quality outputs. One artist (R091) states that AI could make creative work more efficient, but warns against over-dependence, specifically for those in the early stages of their career. Another respondent (R006, non-CI) suggests that AI should only be used for certain parts of the creative process to preserve authenticity. To a large extent, GenAI is particularly beneficial for rapid ideation and serves as a valuable source of inspiration, complemented by the promising technology that can yield promising results. Meanwhile, some respondents acknowledge that AI opens up new business opportunities by facilitating more diverse content creation, specifically for non-creative workers.

Despite recognising AI’s benefits and capabilities, nearly half of the respondents oppose its use in commercial settings. Strong reactions come from those who believe using AI violates ethical and legal boundaries. A graphic designer (R162) states that selling AI-generated works feels unethical because the creative process is largely automated, with minimal human involvement. An author (R163) notes that AI-generated works should not be commercialised until the government establishes legal guidelines. At the same time, another respondent (R116, non-CI) cautions about risks of copyright infringement and creative theft. Beyond that, an artist/craftsman (R501) mentions violating the artist’s code of ethics, and a lecturer (R301) demands proper attribution and honest disclosure of AI involvement in commercial projects. These views corroborate the respondents’ preference for personal use.

Another primary reason is a lack of originality and integrity, which overlaps with another theme about devaluing human creative skills. Since creativity is a trait that makes us humans, which is developed throughout the years of practice, there is disagreement on AI’s growing intervention in such a human process. For instance, “For personal use, simply satisfying ourselves is probably not a problem, but once it gets into the professional realm, it feels unfair to those who spend lots of time practising to create the works. For instance, many webcomic platforms prohibit the usage of AI in assessing works they deem qualified to be published,” (R157, author).

Consequently, over-reliance on AI in commercial production is perceived as a threat to the advancement of creative skills. An artist (R338) predicts widespread AI adoption could blur the line between authentic and AI-generated works, diminishing creative value and weakening artistic identity. Similar to the notion of homogenisation (Boutier, 2025), this could lead to a loss of creative distinctiveness over time, resulting in generic outputs rather than products that reflect each artist and designer’s personal style. Another respondent (R505) argues that AI reduces creative competitiveness by making production too easy, which prompts clients to value design works even less commercially.

This devaluation poses a further threat to the creative industries. Unlike industries that depend primarily on natural capital (e.g. oil, agriculture) or physical capital (e.g. manufacturing, construction), the creative industries are uniquely driven by human capital. Their value is rooted in individual creativity, talent, and skill, making people their most critical asset. An author (R411) states that AI’s widespread use in commercial settings could threaten the viability of creative businesses. This reflects Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma (1997), where disruptive technologies challenge established industries by lowering costs and increasing production efficiency, but at the potential cost of professional displacement.

CREATIVE DISPLACEMENT

[…]

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study has answered three main objectives: (1) exploring public sentiments and attitudes towards AI-generated design works, (2) identifying perceived advantages and limitations of Generative AI in the creative industries, and (3) assessing the perceived potential of Generative AI to replace designers. It reveals the Indonesian public’s ambivalent sentiments towards the use of GenAI in the design creative industries cluster.

Quantitative findings indicate that GenAI is more acceptable for personal use (M=5.43, SD=1.58) than for commercial purposes (M=4.78, SD=1.84), and that the potential for GenAI to replace designers raises a quite significant concern (M=5.2, SD=1.70). These results demonstrate a complex interplay between enthusiasm for innovation and anxiety over its implications, particularly for professional creatives. To frame this complexity, this paper introduces the term “designer’s dilemma,” referring to the twofold tension creative professionals face in the age of GenAI. The first is the dilemma of uncanniness, where AI-generated content, especially in cases such as photo and video manipulation or virtual influencers, evokes discomfort due to its overly realistic, overly typical, or emotionally flat output. Respondents also express concern that AI cannot authentically represent cultural or religious contexts, as it lacks contextual understanding even when the technical quality is high.

The second is the dilemma of pragmatism, where GenAI is favoured for its speed, affordability, and accessibility, even by those who express ethical concerns. The public’s willingness to adopt GenAI, driven by practical benefits and the absence of precise regulation, alongside the existing challenges of working as creative labourers, indirectly pressures designers to adapt or risk becoming obsolete. This higher urgency particularly emerges in fields such as graphic design, where the production process is relatively straightforward and can be easily automated. In contrast, creative sectors that involve complex workflows, such as product design, interior design, or architecture, are perceived as less vulnerable due to their inherently iterative, collaborative, and technical nature. Still, this study underscores the importance of protecting human designers from being replaced by machines and ensuring the authenticity of design works such as by disclosing AI-generated works.

The study finds that acceptance towards GenAI adoption varies across creative industry sectors. While respondents appreciate GenAI’s efficiency, speed, and accessibility, particularly for ideation, they are less accepting in areas where emotional meaning, connection with authors, or cultural depth are critical. This requires specific research that treats each cluster as a distinct ecosystem with its own unique characteristics and challenges.

The findings also expose a critical regulatory gap. Although many respondents express a willingness to comply with laws and ethical guidelines if such frameworks existed, the current vacuum brings a pragmatic attitude of accepting and using AI-generated works for commercial purposes despite ethical concerns. This absence of clear boundaries not only leaves professionals vulnerable to displacement but also fails to cater to the public’s demands for clear regulations.

Ultimately, the adoption of GenAI in the creative industries cannot be guided solely by economic efficiency. It requires thoughtful regulation, ethical literacy, and cluster-sensitive policies. The designer’s dilemma encapsulates the need for a balanced approach, addressing both the discomfort of uncanniness and the ethical tension driving pragmatic adoption in the absence of guidance. As the creative landscape evolves, this study calls for a shift from reactive adaptation to proactive governance, anchored in evidence-based insights. In doing so, it offers an opportunity not only to regulate AI but also to rehumanise creativity in the current technological landscape that might threaten to dehumanise it.

FULL PAPER

Download link here

HOW TO CITE

Wiradarmo, A. A. (2025). Designer’s dilemma: Uncanniness and pragmatism in public perception of Generative AI in Indonesian creative industries. Jurnal Sosioteknologi, 24(3), 385-401.

REFERENCES

On the full paper

Leave a comment